- Home

- Peter Lerangis

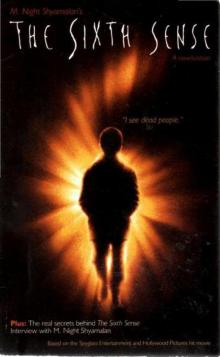

The Sixth Sense

The Sixth Sense Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

About the Author

About the Screen Writer

Director's Cut:Secrets of The Sixth Sense

Back Cover

On the night his life changed forever, Cole Sear was fast asleep. The air carried through his window the feel of a city in autumn - rain-soaked leaves, burning fireplaces, and car exhaust. Tonight, for a change, sleep had come easily. A little too easily. Down the hallway and just past the living room, his mother lay half awake, one ear cocked toward Cole's room. One scream, one gasp, one thump of a bare foot on the floor would send her running. For Lynn Sear, this night was the same as all others. She was worried about money, about her jobs, about her divorce, and always - always - about Cole.

Their apartment was a little small, a little dark, a little messy. It occupied part of the first floor of a brick rowhouse on the north side of South Philadelphia. Since her divorce, Cole and his mom had worked hard to make a cozy and loving home, a perfect nest for two.

They hadn't planned on all the visitors. Hadn't invited them. But still they came.

They came often and whenever they pleased. They never announced themselves, and they certainly weren't welcome. Only Cole could see them.

To their credit, they never bothered Lynn. They weren't interested in her, so she never even knew they were there.

They called, instead, on Cole.

But tonight, so far, they were silent.

In Center City, Philadelphia, about one mile and a couple of tax brackets away from the Sears' neighborhood, Dr. Malcolm Crowe and his wife, Anna, lived in a townhouse with a wide, welcoming stoop. It was neither the smallest nor biggest house on the street, and it was known by the neighbors chiefly for the light that often burned all night in Malcolm's third-floor study.

In a city that crawled with psychotherapists, Dr. Crowe's name stood out. His success rate was legendary. His appointment book was full for months.

Lynn Sear had known about him for years. So had nearly every other parent of a troubled child. Many called him in a panic, and most were politely referred to other therapists with less crowded schedules. But Lynn believed her son needed the best, and she'd been persistent. One month from now, Cole had an appointment to see Dr. Crowe, due to a last-minute cancellation. Dr. Crowe had already interviewed Lynn over the phone about her son. She knew she'd been lucky. Today Dr. Crowe had been honored in a public ceremony at city hall. With all the publicity, he would soon be unreachable.

That night, as Cole and Lynn slept, Anna Crowe descended into the basement and flicked on a light. It was a dank, dismal place, empty but for a well-stocked wine rack. She had always meant to do something about the space. It had potential.

Anna shivered. The room was awfully cold for an autumn night - a damp, wintry cold that sent a chill down her spine.

She glanced over the wine bottles. There. A Beaujolais Villages, good vintage, Malcolm's favorite.

As she raced back upstairs, she shut the door tight behind her.

Her husband was sprawled on the living room floor. He was thirty-eight years old but his smile had the confident glint of a man half his age, and his sturdy physique attested to regular weekend rowing on the Schuylkill River. The only signs of approaching mid-life were the lines on his face, lines that told of the sleepless nights he spent unraveling children's problems to which there were no simple answers.

Tonight Malcolm had vowed not to set foot in his study. Tonight he'd promised to celebrate. Anna saw themselves as Inner and Outer people. As Malcolm was dedicated to the mind's deepest mysteries, Anna was dedicated to its artistic expression. Her antique gallery was small but it had a growing reputation. She'd saved some of her best work for their house, restoring every detail - the dark polish of the wainscoted wooden walls, the fiery facets of the crystal foyer chandelier, the delicate coziness of the Persian rugs. Malcolm refused to call it a restoration. He called it Annatomic Reconstruction-Anna put the wine on the coffee table and slipped on a cardigan that had been hanging over a chair. She handed Malcolm a Liberty Rowing Club sweatshirt from the sofa. "It's getting cold," she said, curling up beside him as he dug the last piece of shrimp from a Chinese takeout container.

Both of them now faced Malcolm's latest award, an ivory vellum certificate framed in dark wood and propped on a chair opposite the coffee table.

"That's one fine frame," Malcolm said. "A fine frame it is. How much does a fine frame like that cost, you think?"

Anna loved when he was goofy like this. He hardly ever did it anymore. "I've never told you, but you sound a little like Dr. Seuss when you're happy."

"Anna, I'm serious," Malcolm said with a self-satisfied smile. "Serious I am, Anna."

Anna's trained eyes easily assessed the value and material of the frame. "Mahogany," she said decisively. "I'd say that cost at least a couple hundred. Maybe three."

"Three?" Malcolm's eyebrows shot up. "We should hock it - buy that CD rack for the bedroom."

A joke, as usual. That was just like Malcolm. Anything that pointed to his achievements became a joke. And he was charming enough to get away with it. What was the point? To keep himself humble? He was already humble. For all his hard work, for all his brilliant insights, for all the parents who cried their gratitude to him over the phone, for all the children whose drawings festooned the living room walls - for all of that, he should let himself reap a reward now and then.

Well, tonight he would. He deserved this award, and Anna was determined to let him know that. To let him feel it. "Do you know how important this is?" she asked. "This is big time. I am going to read this certificate for you."

"I sound like Dr. Seuss?" Malcolm leaned in to tickle her.

Anna deftly slid out of his reach. "'In recognition for his outstanding achievement in the field of psychology, his dedication to his work, and his continuing effort to improve the quality of life for countless children and their families, the city of Philadelphia proudly bestows upon its son, Dr. Malcolm Crowe' - that's you - 'the mayor's citation for professional excellence.' Wow .. . they called you their son."

Malcolm nodded. "We can keep it in the bathroom."

"This is an important night for us," Anna insisted. "Finally someone is recognizing the sacrifices you made - that you have put everything second, including me, for those families they're talking about."

Malcolm's hands drifted lightly, playfully, over her cheek. She hated reminding him about his "sacrifices." It was the only thing they ever fought about, really - the forgotten dinner dates, the chronic lateness, the last-minute cancellations. But it was the truth. They always told each other the truth. She knew what he was like before she'd married him. For better or for worse, they'd said. Overall, it had been worth it.

"They're also saying that my husband has a gift," Anna continued, taking his hand. "Not an ordinary gift that allows him to hit a ball over a fence, or a gift that lets him produce beautiful images on canvas. Your gift teaches children how to be strong in si

tuations where most adults would piss on themselves. I believe what they wrote about you, Malcolm."

Her eyes were brimming with tears. Malcolm wrapped her in a soft embrace. "Thank you," he said.

"Sorry. There wasn't supposed to be any crying. This is a celebration."

Malcolm grinned. "I would like some red wine in a glass. I would not like it in a mug. I would not like it in a jug."

Anna broke out laughing. He'd done it again. She wanted to smack him. She loved him.

They were giddy as they entered the bedroom. Giddy and playful. Anna danced, her light purple dress swinging as lazily as the room's indigo curtains in the autumn breeze.

For the millionth time Malcolm marveled that she had ever agreed to marry him. In the soft bedroom light, she was exquisite. She was always exquisite. Her skin had the translucence of pearl, her hair a liquid-brown richness that framed her face in the shape of a heart. She was teasing him with her eyes - eyes that could be both playful and fierce, intelligent and patient, open and direct yet full of silent, unanswerable mysteries. In their years of marriage Anna had never looked at him the same way twice. She kept things exciting.

Tonight she was in a good mood. But she was cold, too, and the wind was brisk, so Malcolm turned to shut the window.

He stopped when he saw the shattered glass.

The window lay in jagged shards on the floor, trailing into the room along the carpet. Nearby the bedroom lamp had been knocked over and broken. Instantly, their playful word was shattered-just like the window. An icy cold chill ran through their veins. They knew.

Anna stopped dancing. "He's still in the house," she whispered.

From behind them, a shadow slid across the floor. Anna screamed.

Malcolm spun around. The bathroom light was on.

Carefully he moved closer. A black shirt lay on the porcelain tiles. Black pants. Unfamiliar clothes.

Talk to him, Malcolm said to himself. Be calm. Show no fear. Don't threaten.

Before Malcolm reached the bathroom, a man stepped into the light. The intruder.

He was a young man of nineteen or twenty, wearing nothing but a pair of white briefs. His body was emaciated and covered with angry scars, his lower lip split by a recent wound. His brown hair, dirty and matted down, had a streak of white at the left temple. Like a meek, guilty child, he stopped stiffly in front of the sink, with bowed head and clasped hands.

Show no fear.

"Anna, don't move," Malcolm said. "Don't say a word." Evenly, calmly, he addressed the young man. "This is Forty-seven Locust Street. You have broken a window and entered a private residence. Do you understand what I'm saying?"

The man looked up. His eyes were glazed and jumpy, in a haggard face twisted with rage.

The voice, however, was what scared Malcolm most. It was the choked, pleading voice of utter despair, a cry supported by words. "You don't know so many things."

I know this voice. I know this desperation. How many times have I seen it?

"There are no needles or prescription drugs of any kind in this house -"

The man turned his crazed, imploring eyes on Anna. "Do you know why you're scared when you're alone?" His face suddenly crumpled, his lips quivering. "I do . . ."

"What do you want'" Anna blurted out.

"What he promised!" the man shot back, pointing at Malcolm.

"My God," Anna gasped.

Malcolm looked closely at the man's face. Something was familiar. "Do I know you?"

"I was ten when you worked with me," the man said with bitterness. "Downtown clinic? Single parent family? I had a possible mood disorder. I had no friends. You said I was socially isolated. I was afraid. You called it acute anxiety disorder. You were wrong!"

Malcolm stepped back. The profile - he knew the profile. He thought back - when? About a decade ago, perhaps ... There were so many faces, so many stones...

"I'm nineteen," the stranger went on. "I have drugs in my system twenty-four hours a day. I still have no friends. I still have no peace. I'm still afraid." He paused, choking back a sob. "I'm still afraid."

"Please give me a second to think." Malcolm's fingers shook as he touched his chin. Ten years old. Nine years ago. Those eyes. . . "Ben Friedkin?"

"Some people called me Freak."

"Ronald? Ronald Sumner?"

"I am a Freak."

Freak. That name. There was a boy back then. A sweet, troubled, difficult case. The boy who always wore a scarf, even in summer... "Vincent - Vincent Gray?"

Surprise shot across the man's eyes.

Malcolm exhaled with relief. "I do remember you, Vincent," he said gently. "You were a good kid. Very smart... quiet... compassionate. Unusually compassionate."

"You forgot cursed!" Tears streamed down Vincent's face. "You failed me!"

Calm him down. Talk to him.

"Vincent, I'm sorry I didn't help you. I can try to help you now."

Vincent turned abruptly. His right hand reached into the sink, and he pulled out a gun.

Malcolm recoiled. Vincent aimed.

The shot shattered the peace of the autumn night. Malcolm fell back onto the bed, clutching his stomach. Anna shrieked in horror.

As she kneeled over her husband, Vincent pointed the gun to his own head and pulled the trigger.

It seemed as if no time had passed at all. But it was a year later, and the trees were brilliant with the changing season.

Malcolm seldom thought about that awful day anymore, about the sound of the gunshot and the way it had changed everything. But he was still a psychologist - despite the horror and bloodshed, he could not stop feeling responsible for Vincent Gray. For all Malcolm's success, he had failed the boy.

Now fate, it seemed, had given him an opportunity to try again.

As he sat on a bench across from a line of brick rowhouses, he reviewed the problems of an intriguing case. It was one of the many he had never been able to follow up on. He vaguely remembered talking to Mrs. Sear. She had been especially eager for her son to see Malcolm as soon as possible.

He could see why.

Malcolm ran his finger down the notes he'd taken of their phone conversation over a year ago. He'd circled all the relevant phrases: Acute anxiety . . . socially isolated. .. possible mood disorder.. .parental status- divorced... communication difficulty between mother-child dyad.

The symptoms were the same, word for word, as Vincent's.

He was nervous about this. He could feel Anna's anger and frustration, the tension that had always existed between them. She thought she was second in Malcolm's mind; she'd told him so.

It wasn't true, of course. But he had a job, he was passionate about it, and he'd been away from it for a long time. In the end, she had always understood that part of him. He hoped she still did.

A life might depend on this case. Perhaps this time, he would do some good. Perhaps he could head off a tragedy before it happened. He didn't know exactly how - but then again, you never went into a patient relationship with answers. First you listened.

As the rowhouse door slowly creaked open, Malcolm looked up.

The boy appeared, peering cautiously into the street. He was small for eight, his hands barely reaching the knob. His glasses certainly didn't help; they were at least three sizes too large.

Malcolm stuffed his notes in his briefcase, then stood up to cross the street's center median.

But the boy was gone, racing down the brick sidewalk as fast as his little legs could carry him. Had he seen Malcolm?

Malcolm gave chase. The boy turned right at the corner. He dodged into a parking lot at the end of the block.

The lot led through the block to the next street, where a large brick church stood. Cole was yanking at the handles, throwing his entire body into opening the solid oak door. He seemed frantic, scared.

Resistance. Not uncommon in a child this age.

Malcolm took a deep breath and followed.

In

side, the church was nearly empty, save for one worshipper in the back and a row of toy soldiers lining the top of a pew in the middle.

Malcolm quietly sat in the pew behind the soldiers. A tiny hand reached up and placed a knight beside a king.

"Deprofundi . . . clamad . . . Domine . . ." Cole was muttering something barely intelligible. Latin, it sounded like.

Don't scare him. Just make conversation.

"You know something about churches?" Malcolm said. "In olden times, in Europe, people used to hide in churches to claim sanctuary."

Cole peered over the pew. His face was small, a bit pinched, his chin tapering to a point. His hair needed a trim, and it looked as though he'd gotten white paint on the back of his head.

But Malcolm was transfixed by the boy's extraordinary eyes. They assessed him through lensless glasses, brown and soulful, with the sad gravity of someone ten times his age.

Malcolm was fairly certain Cole would bolt. Instead the boy spoke up in a small voice: "What were they hiding from?"

"Oh, lots of things, I suppose," Malcolm answered. "Bad people, for one. People who wanted to imprison them, hurt them."

This boy headed to a church when he was afraid. He craved sanctuary. Protection. From what? Was his mother attacking him? Not likely - why would she have set up the appointment? The kids at school, perhaps. Surely a boy his size and temperament would be picked on.

But bullies generally began inflicting serious physical injury at a later age - fifth or sixth grade, not third.

Perhaps Cole was injuring himself.

Malcolm would have to visit the school. Observe the mother in the home. Things he may not have done sufficiently ten years ago.

The parallels were uncanny - right down to the patch of white hair. There had to be an explanation, some connection Malcolm was missing.

This case was going to need a long time and a lot of energy.

At number 47 he bounded up the stoop and unlocked the front door. The entrance hall was dimly lit, and a mountain of mail stood precariously on a table. At the top of the stairway, a soft light shone from the bedroom. Anna was home.

"It's me!" he called out.

The Orphan

The Orphan Lost in Babylon

Lost in Babylon Last Stop

Last Stop Antarctica Escape from Disaster

Antarctica Escape from Disaster Rewind

Rewind Driver's Dead

Driver's Dead The Dead of Night

The Dead of Night The Promise

The Promise The Yearbook

The Yearbook Lab 6

Lab 6 The Tomb of Shadows

The Tomb of Shadows The Curse of the King

The Curse of the King Max Tilt: Fire the Depths

Max Tilt: Fire the Depths The Fall Musical

The Fall Musical The Chaos Loop

The Chaos Loop Island

Island The Sixth Sense

The Sixth Sense Wtf

Wtf War

War Star Trek IV, the Voyage Home

Star Trek IV, the Voyage Home The Sword Thief

The Sword Thief The Viper's Nest

The Viper's Nest The Select

The Select The Legend of the Rift

The Legend of the Rift I.D.

I.D. The Sword Thief - 39 Clues 03

The Sword Thief - 39 Clues 03 The 39 Clues Book 7: The Viper's Nest

The 39 Clues Book 7: The Viper's Nest Antarctica

Antarctica Seven Wonders Journals: The Select

Seven Wonders Journals: The Select Seven Wonders Book 1: The Colossus Rises

Seven Wonders Book 1: The Colossus Rises Enter the Core

Enter the Core![39 Clues _ Cahills vs. Vespers [03] The Dead of Night Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/39_clues_cahills_vs_vespers_03_the_dead_of_night_preview.jpg) 39 Clues _ Cahills vs. Vespers [03] The Dead of Night

39 Clues _ Cahills vs. Vespers [03] The Dead of Night Fire the Depths

Fire the Depths 80 Days or Die

80 Days or Die Seven Wonders Book 3

Seven Wonders Book 3