- Home

- Peter Lerangis

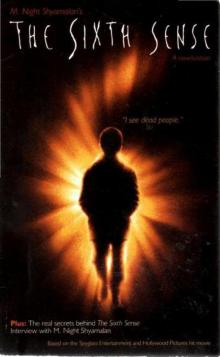

The Sixth Sense Page 5

The Sixth Sense Read online

Page 5

"Yes?"

"You haven't told bedtime stories before."

Malcolm's face reddened. "No."

"You have to add some twists and stuff. Maybe they run out of gas."

"No gas ... hey, that's good." Malcolm nodded his head. Twists. The father must have been a good yarn spinner. Perhaps this was one of the reasons for Cole's active imagination. So, say the car has no gas, then what?

"Tell me a story about why you're sad," Cole said.

Malcolm's thoughts screeched to a halt. "You think I'm sad? What makes you think that?"

"Your eyes told me."

"I'm not supposed to talk about stuff like that." As the words left his mouth, Malcolm realized how dumb they sounded. It was his standard response -all the books said that psychotherapists were supposed to keep their personal lives out of the professional relationship.

But if Malcolm were to get through, he would have to take risks. He was already following the kid around now, inserting himself into every aspect of Cole's personal life. This had gone beyond a clinical relationship. Cole was curious. Why not let him know who Malcolm Crowe really was, let him see past the so-called expert to the human being underneath?

Cole was cocking his head, waiting for an answer.

Malcolm looked away, his thoughts racing back over the past year. "Once upon a time," he began, "there was a boy named Malcolm. He worked with children. Loved it more than anything. Then, one night, he finds out he made a mistake with one of them. Didn't help that one at all. He thinks about that one a lot. Can't forget."

A broken window. That was how it all started. A broken window and a broken young man. Then - what? A broken marriage. Two broken lives. And a trail of pieces to pick up.

"Ever since then," Malcolm continued, "things have been different. He's become messed up - confused, angry. Not the same person he used to be. His wife doesn't like the person he's become. They barely speak anymore. They're like strangers."

Malcolm felt his eyes moisten. Another broken rule - you never let the patient see your personal suffering.

He turned and met Cole's rapt gaze. "And then one day, this person Malcolm meets a wonderful boy who reminds him of that one. Reminds him a lot of that one. Malcolm decides to try to help this new boy. He thinks maybe if he can help this boy, it would be like helping that one, too."

Malcolm stopped. That was it. The whole story in a nutshell.

The ball was in Cole's court now.

"How does the story end?" the boy asked.

"I don't know ..." Malcolm slowly shook his head. His words trailed off into a long, swollen silence.

"I want to tell you my secret now," Cole whispered.

Malcolm was jolted out of his haze. He hadn't expected this. "Okay."

Cole paused. His face was ashen. "I see people," he said, his Voice a whisper. "I see dead people. Some of them scare me."

I see dead people . . .

"In your dreams?" Malcolm asked.

Cole shook his head no.

"When you're awake?"

Cole nodded.

"Dead people, like in graves and coffins?"

"No. Walking around, like regular people. They can't see each other. They only see what they want to see. They don't know they're dead."

"They don't know they're dead?"

"I see ghosts. They tell me stories - things that happened to them. Things that happened to people they know. They always want something from me."

Malcolm's mouth became suddenly dry.

Delusions. Voices. This was out of left field. Different than Vincent Gray. Vincent had never talked about ghosts.

"How often do you see them?" Malcolm asked, trying to keep his professional cool.

"All the time. They're everywhere." Cole's voice was barely audible now. "You won't tell anyone my secret, right?"

"No," Malcolm replied.

"Will you stay here till I fall asleep?"

Malcolm nodded. He sat rock-still as Cole pulled up in his blanket and turned on his side. At that moment, Malcolm didn't want to be alone either.

Sleep came quickly for the boy, and soon Malcolm left. He made his way quickly through the neon-washed corridors of the hospital, not saying a word until he was on the street.

At the corner he pulled out his pocket voice recorder and put it close to his mouth.

"Cole," he said under his breath. "His pathology is more severe than initially assessed. He's suffering from visual hallucinations, paranoia - symptoms of some kind of school-age schizophrenia. Medication and hospitalization may be required."

He pressed the off button, dropped the machine in his pocket, and muttered the words he didn't dare record:

"I'm not helping him."

Lynn pushed the door open with her hip. She was carrying Cole on her shoulder, his red cotton sweater under his head as a pillow. This was a lot harder than it used to be when he was little, but she did it with grace and speed, slipping into the front hall and heading straight for his bedroom.

Mrs. Sloan hadn't been too harsh, thank goodness. She was a mother, too, and she recognized the agony that Lynn felt. By the end of the question-and-answer session, they were both crying.

Lynn had hoped she could take Cole away from the sterile hospital room early enough so that he could fall asleep in his own bed. But by the time she had completed the paperwork and gotten to his room, he was already snoring.

No matter. He'd wake up tomorrow to Mama and Pop-Tarts, home sweet home. No more hospital walls. No more having to face those horrible boys at their awful homes.

Sebastian was already snoozing on the bedspread, warming it up for Cole. Gently Lynn lay her son down next to the puppy and rested Cole's head on his pillow.

She took his red sweater from her shoulder and folded it neatly. Her finger slipped through a moth hole she wasn't aware of. Odd. The sweater was brand-new.

Holding it up to the lamp, she saw that it wasn't a moth hole at all. It was a rip. Parallel to it were two others, as if the sweater had been torn from Cole's neck by very strong fingers.

What on earth had happened to him on those stairs?

Her eyes focused on the back of Cole's T-shirt. It, too, was ripped in three places, corresponding exactly to the holes on the sweater.

She pulled back the shirt. Three long, deep scratches had gouged his skin diagonally across his left shoulder blade.

Finger marks. Through the sweater and shirt.

How vicious did a kid have to be to leave these - how full of hate and evil? Was this the reason they had invited her child to the party? To abuse him and lock him in a closet? To hospitalize the kid from the other side of the tracks? Did this make them feel better about themselves?

No way was she working two jobs - scraping by on five hours' sleep a night - to send her son to a school where he was a target for spoiled, rich hoodlums.

Without waking Cole, she carefully removed his tattered shirt. She could see the hospital had treated the cut, but the bandage had fallen off. Quickly she retrieved one from the bathroom, applied it, and pulled the covers over her son.

Then she stormed into her bedroom and tapped out the Winthrops' phone number. At this hour, she'd wake someone, but she didn't care.

"Hello?" said a groggy voice.

"Hi, this is Lynn Sear, Cole's mother. I wonder if we could talk about your son and his goddamn friends keeping their hands off my boy?"

Cole's eyes opened. He was home. Mama had come and gotten him.

That was good, because he really had to go to the bathroom. He had held it in because he hated the hospital bathroom. He hated the hospital, period. There was no place to hide from them. They were all over the place. He could see them when he looked out the window, wandering the corridors in the hospital wing across the airshaft.

It was a good thing Dr. Crowe had visited. Otherwise he might not have fallen asleep.

He jumped off his bed and walked out the door. Qu

ickly he checked the hallway, because you never knew.

Then, tiptoeing as fast as he could, he ran across the hall and did his business.

What a relief.

As he reached out to flush, he heard a movement.

Behind him. In the hallway.

He turned slowly. It was freezing cold, and he felt goose bumps on the flesh of his arms and scalp. As he leaned on the doorjamb, peering into the hallway, he could see his breath. That was a sign.

He eyed the red tent inside his bedroom door. The saints were in there, and Jesus and Mary and all those other figures from church. He would be safe there. Safe from the dead people.

To his left, a shaft of light slanted across the carpet from the kitchen entrance. He heard the sound of oil popping on a skillet, vegetables being chopped.

Mama - at this hour?

Lately she'd been having insomnia. He and she had that in common. Sometimes they sat in the kitchen together and had hot cocoa. She didn't usually cook anything, though.

Cole crept toward the kitchen and looked in.

Her back was to him. She was wearing a bathrobe, leaning over the stove. All the kitchen cupboards and drawers were open.

"Mama?" he said. "Dream about Daddy again?"

She stiffened.

"DINNER'S NOT READY!"

As she whirled around, Cole lurched backward. It wasn't Mama at all.

She glared at him through bloodshot eyes, one of them black and blue. Her face was hideous, old and ugly and all scratched up. It was the lady who opened all the cabinets, the one who'd visited a few mornings ago, when Mama had seen the spot on his tie.

"What are you going to do?" she demanded, her voice harsh and sarcastic.

His heart pounding wildly, Cole stepped backward, toward the hallway.

"YOU CAN'T HURT ME ANYMORE'" With a demented grin, she thrust her arms forward, palms up.

Her wrists had been slashed open with a knife.

Cole nearly fell as he scrambled out of the kitchen. The tent. He had to get to the tent.

He ran into his bedroom and dived through the tent flap. His whole body shook. He pulled the flap closed, then snatched a flashlight off the floor and flicked it on.

The light, reflected off the sheets, cast the interior in a deep red. Beside him, lined up carefully on a wooden rack, were his figurines. They smiled down at him. Everything is all right, their faces said.

"De profundis clamo ad te Domine ..." Cole began whispering

"Okay, kids, house lights to half..." Mr. Cunningham said in an excited whisper. "We've got a big crowd out there. Don't be nervous. House lights off... and curtain!"

Stacey Stratemeyer began yanking the curtain open. Cole peeked out from behind his body-size cardboard monkey cutout. The stage lights washed over the seats of the darkened St. Anthony's auditorium, reflecting against a sea of camcorder lenses.

He saw Dr. Crowe and Mama, both clapping and grinning proudly as they read the banner draped across the stage: the third and fourth

GRADE PRESENT- RUDYARD KIPLING'S THE JUNGLE BOOK.

"Break a leg, kids!" Mr. Cunningham called out, and he and nudged Tommy Tammisimo to the stage.

Tommy strutted out with a big, conceited grin. "There once was a boy," he exclaimed in a British accent, "very different from the other boys. He lived in the jungle and he could speak to the animals!"

That was Cole's cue. He crab-walked onto the stage along with all the other kids playing trees, native villagers, giraffes, tigers, and elephants.

It was a small part. But he knew he was the most convincing on the stage.

After the play, after Mama had kissed him and told him what a great actor he was before running off to her job, Cole took a long time getting ready to leave. He liked being on stage. It was a little like being in the tent, or in church. He felt safe, surrounded by light and good energy. He couldn't wait for "Young King Arthur," the drama club presentation later this month. Maybe he'd have a bigger role this time. At one time he'd wanted Mr. Cunningham to cast him as Galahad or Lionel or even Mordred - but after Cole's outburst in class, he was more likely to be a dragon or a horse. Or the stone embedded with the sword. Tommy would love that.

Dr. Crowe met him at the stage door and walked with him through the school. The corridors were empty now, and their footsteps echoed against the floor tiles.

"Did you think the play sucked big time?" Cole asked.

"What?" Dr. Crowe said.

"Tommy Tammisimo acted in a cough syrup commercial. He thought all of us were self-conscious and unrealistic. He said the play sucked big time."

"I know every child is special in his or her own way, but Tommy sounds like a punk," Dr. Crowe said. "I thought the play was excellent. Better than Cats."

"Cats?"

"Never mind."

Whatever. Cole couldn't help smiling. It was nice having Dr. Crowe on his side.

They took a left and walked silently toward the school's side exit, near the gym.

"Cole," Dr. Crowe said, "I was really interested in what you told me in the hospital. I'd like to hear more about it."

Cole had to think for a moment.

The ghosts - they had started talking about the ghosts. Why did Dr. Crowe want to talk about them now?

Cole didn't quite know how to tell Dr. Crowe about them. He'd have to be very careful.

As they passed a narrow stairway, Cole felt a chill.

They were here.

He froze, standing absolutely still. He heard the squeak of the dangling ropes, and he knew.

He had seen them before, in this same place. Right above those stairs was the chamber. The place where the people were punished.

He wished he and Dr. Crowe had gone out the front door, not here.

"What's wrong?" Dr. Crowe asked.

Cole tried not to look but he couldn't help it. There were three of them, a black family - man, woman, and boy. Runaway slaves, probably. They were barefooted and dressed in old raggedy clothes, hanging from the ropes used to strangle them to death. And they were staring.

Cole forced himself to look at the floor as he pointed up to the bodies.

Dr. Crowe turned to look. "Is something in there? What is it? I don't see."

"Be real still," Cole said. "Sometimes you feel it inside - like you're falling down real fast, but you're really just standing still.... Do you ever feel prickly things on the back of your neck?"

"Yes?" Dr. Crowe said.

"And the tiny hairs on your arm," Cole continued. "You know when they stand up?"

"Yes?"

"That's them. When they get mad, it gets cold."

Cole held tight, squeezing all his muscles. To keep away the cold. And the falling sensation. And the fear.

Cole hoped Dr. Crowe would be different - that he would see what Cole could see.

But just like the others, he couldn't see.

"I don't see anything," Dr. Crowe said, squinting anxiously at the landing, the ceiling, the shadows of the hallway.

The three bodies dangled heavily, their necks bent and broken, their eyes wide and buggy and staring straight ahead.

The eyes. Not the eyes.

"Please make them leave," Cole said.

Malcolm took his hand and shot a look back up the stairs. "I'm working on it."

Lynn pulled a nice piece of juicy roast beef off the stove. She'd bought a big supply of meat during the sale at the A&P this week. Cole's color had been off lately, and the protein and iron would do him good.

His eyes were glued to a cartoon on the kitchen TV. As she served him his meal, he barely noticed. That was okay. At least he was smiling. She was grateful for that. He was always easier to talk to when he was in a good mood.

And she had some serious things to talk to him about.

It was suddenly very chilly in here. As Lynn returned to the stove for her own plate, she de-toured to the thermostat and turned it way up. "I don't care what they say," she murmured. "Thi

s thing is broken."

A familiar tinny, high-pitched voice cried out from the TV: "Mommeeeee, my throat hurts!"

Tommy Tammisimo. In full color. Standing in bedroom doorway, dressed in pj's. Again. They played that darn commercial all night long. She and Cole had seen it a million times.

On the screen, the actors who played the perfect parents exchanged a knowing glance, not a hair out of place as they left their bed, took Tommy to the bathroom, fed him cough syrup ... and now the syrupy music ... here comes the friendly announcer....

"Pedia-ease Cough Suppressant," a deep voice intoned. "Gentle, fast, effective."

Miraculous was more like it. Cut to Mr. and Mrs. Yuppie the next morning, looking out their spotless window as a now-cured Tommy frolics in the yard with his dog. He waves ecstatically, they wave back....

Cole threw a shoe at the screen. The TV lurched backward, the plug yanked out of its socket, and the image went blank.

Lynn didn't like him throwing things. Violence was not the answer. But she let this one go. Tommy deserved it.

She did mind, however, that Cole was wearing his father's winter gloves while he tried to drink his milk. Her ex-husband had been in such a hurry to leave, he hadn't had the decency to remove all his possessions and spare her the grim reminders. Now Cole insisted on wearing his stuff all the time. "Take 'em off," she said.

Cole obediently removed the gloves and placed them next to his milk glass.

"I don't want them on my table," Lynn snapped.

As Cole put them on the floor, Lynn pulled out a chair and sat opposite him. They ate in silence for a moment as she composed mentally what she needed to say. He had been taking things from her bedroom lately, and it had to stop.

She knew he had been sneaking religious figures from the church. She'd talked to Father Manahan about it, and he'd asked in a tactful way if Cole had ever shoplifted. When Lynn told him no, he'd smiled and said not to worry. Cole was a good boy and he clearly needed the comfort of the saints. When he was older, his conscience would lead him to confess, and he would return the figures. The church, of course, would be there for him with forgiveness. Let the church be there for him now.

But now he'd been using his sticky fingers at home. And that was just plain wrong.

The Orphan

The Orphan Lost in Babylon

Lost in Babylon Last Stop

Last Stop Antarctica Escape from Disaster

Antarctica Escape from Disaster Rewind

Rewind Driver's Dead

Driver's Dead The Dead of Night

The Dead of Night The Promise

The Promise The Yearbook

The Yearbook Lab 6

Lab 6 The Tomb of Shadows

The Tomb of Shadows The Curse of the King

The Curse of the King Max Tilt: Fire the Depths

Max Tilt: Fire the Depths The Fall Musical

The Fall Musical The Chaos Loop

The Chaos Loop Island

Island The Sixth Sense

The Sixth Sense Wtf

Wtf War

War Star Trek IV, the Voyage Home

Star Trek IV, the Voyage Home The Sword Thief

The Sword Thief The Viper's Nest

The Viper's Nest The Select

The Select The Legend of the Rift

The Legend of the Rift I.D.

I.D. The Sword Thief - 39 Clues 03

The Sword Thief - 39 Clues 03 The 39 Clues Book 7: The Viper's Nest

The 39 Clues Book 7: The Viper's Nest Antarctica

Antarctica Seven Wonders Journals: The Select

Seven Wonders Journals: The Select Seven Wonders Book 1: The Colossus Rises

Seven Wonders Book 1: The Colossus Rises Enter the Core

Enter the Core![39 Clues _ Cahills vs. Vespers [03] The Dead of Night Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i1/04/02/39_clues_cahills_vs_vespers_03_the_dead_of_night_preview.jpg) 39 Clues _ Cahills vs. Vespers [03] The Dead of Night

39 Clues _ Cahills vs. Vespers [03] The Dead of Night Fire the Depths

Fire the Depths 80 Days or Die

80 Days or Die Seven Wonders Book 3

Seven Wonders Book 3